Rebirth from Chaos: Neil Young's Journey Through The Ditch

A chaotic period can be one of the only times when the self is fully understood. Caught in the steady flow of life with all of the responsibilities, events, and material pleasures it entails, it can be easier to simply ride the waves and totally ignore who we are in the process. It’s when a storm begins to brew that comforting equilibrium gets irreversibly shattered, where we are forced to confront ourselves head-on. In a personal crisis, we are mentally trapped within the eye of a hurricane: destruction and disarray surround us, but within the far less destructive confines of our mental space, every part of our being becomes uncomfortably magnified with an almost terrifying level of clarity. Some might find such periods depressing and painful, but at the same time, they can be a transformative period of growth, reassessment, and self-discovery. When all the wounds and scars have been mended, one comes out not only stronger but more self-assured than ever before.

If there is a testament to the subtle healing power of these periods, it is the enduring power of Neil Young’s output during his tumultuous “classic era.” From the jingly-jangly warmth of “Burned” back in 1966 to the apocalyptic strikes of blood-soaked distortion in the Rust albums of 1979, he encountered more setbacks, hit more dead-ends, and suffered through more pangs of disillusionment than most people do in their entire lives. At the same time, it was just as much a period of searching, trying to find himself and his life purpose in the troubled decades of the ‘60s and ‘70s. As a result, Young’s “classic period” became a rich, kaleidoscopic portrait of himself, with each album feeling like another shard in the greater picture of his life. It would take great hardship and looking deep within himself through three introspective albums called the ditch trilogy (1973-1974) to complete it, but this era was also a period of great healing toward a future he wanted to live in.

Neil’s turmoil can be felt from the earliest of his compositions, as he started his career in his hometown of Winnipeg, playing in instrumental rock bands and folk clubs. However, even then, Neil felt the looming, irreversible fate of reaching adulthood, feeling lost on what he would make out of his life. The quiet, insecure contemplation of “Sugar Mountain” documents the loss of innocence, the soft strum and murmur of his vocal performance subtly revealing anxiety about leaving the comforts of childhood for an intimidating world. All of this would change with 1967’s “Summer of Love” and the psychedelic movement sweeping the Western music world off its feet. This sudden cultural shift marked the beginning of Young’s pressure to compromise his burgeoning artistic vision and bleeding personality to follow contemporary musical trends. While the brutal, distorted pummeling of “Mr. Soul” and the noisy experimentation on Stills’s “Everydays” felt like Young nourishing his artistic impulses, he also contributed to Buffalo Springfield Again. “Expecting to Fly” and “Broken Arrow” lush, romantic epics, unlike anything he would put out since. Both songs are truly impressive achievements of their era, scaling cosmic heights with expansive soundscapes while still sounding like they’re coming from the inner recesses of his mind. At the same time, Young was merely moving with the tide of the trends and no matter how excellent his contributions were, it feels like the musician was taking ideas from the Moody Blues’ or Brian Wilson’s cookbooks rather than following the guide of his own muse.

All of this would change with 1967’s “Summer of Love” and the psychedelic movement sweeping the Western music world off its feet. This sudden cultural shift marked the beginning of Young’s pressure to compromise his burgeoning artistic vision and bleeding personality to follow contemporary musical trends. While the brutal, distorted pummeling of “Mr. Soul” and the noisy experimentation on Stills’s “Everydays” felt like Young nourishing his artistic impulses, he also contributed to Buffalo Springfield Again. “Expecting to Fly” and “Broken Arrow” lush, romantic epics, unlike anything he would put out since. Both songs are truly impressive achievements of their era, scaling cosmic heights with expansive soundscapes while still sounding like they’re coming from the inner recesses of his mind. At the same time, Young was merely moving with the tide of the trends and no matter how excellent his contributions were, it feels like the musician was taking ideas from the Moody Blues’ or Brian Wilson’s cookbooks rather than following the guide of his own muse.

Disillusioned with band infighting and struggling with an unquenched desire for artistic independence, Young contributed two self-penned songs to Buffalo Springfield’s final album before his departure from the band. Upon jamming with members of a psych/folk-rock band the Rockets, he found an almost telepathic guitar-weaving synergy with the band’s guitarist Danny Whitten. Young quickly recruited the Rockets to form his iconic backing band, Crazy Horse. The fledgling ensemble debuted on the seminal Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere, an album crackling with explosive inspiration. On the two earth-shattering guitar jams (“Down By The River” and “Cowgirl In The Sand”), Whitten and Young would ricochet piercing riffs off of each other, valuing emotional minimalism and brutal expressivity above technical perfection. From the thick raunchy primitivism of “Cinnamon Girl” to the world-weary country rock of the title track to the heart-stopping meditative beauty of “Round & Round,” Young inched closer to finding his role within the musical world while refining how roots rock would be played forever.

However, this exciting self-exploration soon came to a grinding halt by the singer-songwriter explosion of the early ‘70s. He was encouraged to join the supergroup Crosby, Stills and Nash, and Déjà Vu, their first album as a quartet, which sold over eight million copies. Suddenly, Young found himself at the center of the soft-rock movement, a trend that doesn’t suit a contemplative iconoclast with a penchant for distortion like himself. Nevertheless, he released After The Gold Rush , an attempt at self-preservation within the rigid bounds of soft rock. It’s an immaculate creation showing the sheer breadth of his compositional and performing talent, but it came at the cost of stifling his ability to dig deeper and express himself in more uncomfortable, vulnerable ways. Despite this regression, the album was both an artistic and commercial success, and it seemed like Young struck the ideal balance of appealing to mainstream culture while still staying an iconoclast.

, an attempt at self-preservation within the rigid bounds of soft rock. It’s an immaculate creation showing the sheer breadth of his compositional and performing talent, but it came at the cost of stifling his ability to dig deeper and express himself in more uncomfortable, vulnerable ways. Despite this regression, the album was both an artistic and commercial success, and it seemed like Young struck the ideal balance of appealing to mainstream culture while still staying an iconoclast.

Unfortunately, this walking on a knife’s edge would prove to be unsustainable. With the comfort of his success and enjoyment of his new life with then-partner Carrie Snodgress, he decided to sell out entirely to the trends with Harvest. Exchanging the bright guiding lights of Bob Dylan and Link Wray for the smoother alternatives of James Taylor and Linda Ronstadt, Young watered down his artistic persona to make it more palatable to the post-hippie audiences of 1972. Indeed, its uninspired decadence received unmatched acclaim. Harvest became the best-selling album of the year and spawned one of the biggest hits of its time, “Heart of Gold”. The record cemented the singer’s status as rock royalty, making him one of the biggest and most popular musical icons of his year.

Nonetheless, while his throne looked glorious from afar, it masqueraded a darker reality within. Unlike his commercially successful peers, Young struggled to cope with the impact of fame and fortune. He found the new middle-of-the-road direction on Harvest suffocating and ultimately capping artistic progress. Instead of working through his deep-rooted emotional problems and exploring the darker corners of his conscience, he was trapped within a style that limited his range of expression. The decaying state of ‘70s American culture only furthered his deterioration, where his musical statements about the Kent State shootings (“Ohio”), the raging Vietnam War (“Soldier”), and the endless victims of drug overdose (“Needle and The Damage Done”) reflected his eroding his faith in humanity. Holding together his easy-going image was not only an enormous emotional burden for the musician but also acted as treason to his own eyes and ears. The cracks in Young’s conscience began to form and it was only a matter of time before the dam would burst wide open.

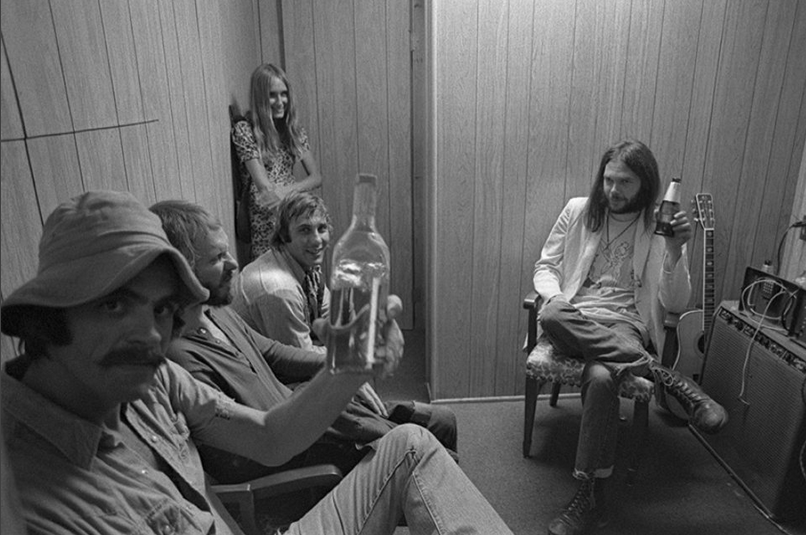

The singer’s mental unfurling catalyzed during n the biggest tour of his career, where he was accompanied by his Harvest-era backing band Stray Gators and Danny Whitten. At the time, Whitten struggled with a painful heroin addiction for years, so intense that he inspired the harrowing, aforementioned “Needle and the Damage Done.” With his condition deteriorating, he was unable to function properly during a concert rehearsal. As a result, Young fired his longtime friend and gave him a plane ticket to go back home and recover. That same night, Young received a call from a coroner that Whitten had died from an alcohol/diazepam overdose. The traumatic effects of this event on Young’s mental health were vast. Whitten was not just a close friend and bandmate to the singer; he forged his artistic identity with him. The spiritual synchronicity he felt when jamming with Whitten on Nowhere unlocked unimaginable artistic capabilities for Young, helping him to find the musical styles that encapsulated who he was. When Whitten passed, it symbolically marketed the crumbling of the early idealism he had in the 60s, and with the new middle-of-the-road pop he was planning to perform for millions, he went against what he and Danny initially stood for. Neil chose to stray off this well-paved road of fame and fortune and dive deep within the ditch, where, over the course of three records, he would try to reconcile his personal problems and find a way out of his sullen state.

Alas, this turbulent tour did not end his freefall into “the ditch.” The cerebral palsy diagnosis of his newborn son was already a lot for the singer to bear, and losing yet another friend, roadie Bruce Berry to a drug overdose fragmented his mental state to the point of near collapse. Desperately needing a vehicle for his intense state of grief, Young recorded the bleakest album of his career, Tonight’s The Night. If Time Fades Away still had some lingering Harvest-isms, this record purged any trace of his slicker past out of his system. With the musician entirely chucking accessibility out the window, the raw expressivity of these crude, dense, bleeding chunks of Young’s soul was excruciating to listen to. The performances were brutally honest confessions, utilizing grimy tones and austere arrangements upon heartbreakingly sincere vocal performances to extract much-needed catharsis. The agonizing whimpering of “Mellow My Mind,” the ghostly sound of “Albuquerque,” and the painful recounting of the title track all reflect how Young and his bandmates attempt to cope with losing their friend. Yet, it’s in the subtlest, quietest moments of the record, like the harrowing acapella coda of “New Mama” and large swaths of silence in “Borrowed Tune,” where you can viscerally feel the disintegration of Neil’s idealism as his deep-rooted sorrow echoes within your bone marrow. It could be argued that this musical funeral was the very first time that Young bared his soul with no strings attached, finally freed from his soft-rock shackles to use his art to express his innermost feelings.

Even within the ink-soaked darkness of Tonight’s The Night, there were gleams of hope for an escape from the ditch. The final three songs of that album show signs of recovery and hope for Young. “Lookout Joe” and the reprise of the title track even sounds triumphant, bracing himself together and pushing through the pain towards a better future. Still, his decaying relationship with his girlfriend and loads of other personal problems needed to be properly dealt with to fully heal himself. Thankfully, he had reached the point where musical sincerity flowed out of him organically, and now, he would use it to climb out of the depths of “the ditch.” Thus, On the Beach became the final chronological part of the “Ditch” album trilogy, detailing his journey out of depression on side two and returning to normal life on side one. Each part would be a phase in his emotional recovery, progressively coming to terms with his life until Young’s sound finally reflected a state of peace.The title track immediately plummets listeners into the twilight zone of a dark psychedelic ocean. The hazy Wurlitzer piano mixed with the hand drum rhythm gives the song an unusual texture, a suffocating heaviness within the deeply personal sonic universe. Its slow, dreary funeral march allows the sound to sprawl over the 7 minutes with ease, sounding like Young is lost and alone within a cold, frigid expanse. The lyrics reflect that he is trapped within an icy internal world inside his own mind. Whether Young faces a crowd of people or a radio interviewer, he still finds himself alone at the microphone. The song gets its structure from the gloomy 12-bar blues tradition, but even then, it is unlike any blues ever performed; There’s no tough macho posing nor venting of frustration present in the song to be associated with the likes of Muddy Waters or Otis Rush. Instead, it is Young drowning himself in his negative thoughts to force himself to process the trauma he endured. Rather than fighting against them or succumbing to their lethal effects, he simply smothers his brain with the darkness to gain immunity to them, no matter how painful it may be.

Slowly and gradually, the effects of this internalization began to pay off on “Motion Pictures.” Finally adjusting his mental health to his chaotic life, Young, for the first time in his life, looked back at his life from an objective frame without losing emotional stability. Traces of sadness and bittersweet humor still linger, but under such a tranquil atmosphere with all those lazily slide guitar licks, they all fizzle away in the bliss of his dissociated state. He became a third-person observer of his own life, languidly sitting back and watching the motion pictures of his life flash by as he begins to make sense of it all. It’s in this numb clarity he becomes truly self-aware. The lyrics indicate Young finally understands that he doesn’t want to be like his self-absorbed peers, and he wouldn’t give a thing to be like any of them. He saw the aimless, peer-pressured trend hopping he had been doing for nearly half a decade and now wanted to end this unhealthy insecurity once and for all. Young was ready to make his way out.

The scars and hardship he endured would begin to heal in the final song, “Ambulance Blues.” The acoustic riff guiding the song has an incredibly complex sense of beauty, feeling as delicately warm as melancholically bittersweet. The singer was bringing himself to a state of peaceful acceptance, yet he was still torn internally. While there was a part of him that still struggled to deal with the events of his ditch period, his mind, body, and soul were ready to enter a whole new plane of existence, transforming into a person who was much more confident, stable, and self-assured. It was inevitable that his past self would have to die to allow for his own rebirth, but without the proper care, he would die a violent, anguished death that would linger on with him forever. This song would be Young’s compassion towards his former self in its final moments, allowing it to rest easy and pass without suffering.

It’s not a surprise that the theme of death causes comparisons of “Ambulance Blues” to Dylan’s “Desolation Row,” but while Dylan used his song to find a common spiritual thread between the ordinary artifacts of our daily lives, Young’s epic folk ballad is recounting the deep contemplations during the last moments of a person’s life. The disjointed set of lyrics are snapshots of past memories, brief moments, or quotes that impacted and stayed with him throughout his life. Yet, there is no dichotomy of the good and bad or happy and sad present in these nostalgic ruminations. He was reaching a state of enlightenment where such differences did not exist: childhood, heartbreak, friendship, political distrust, disillusionment, optimism, the pain and beauty of life all belonged to the same cosmic order, and it was a precious privilege to experience all the facets of life, no matter the ups and downs that came with it. It was this realization of acceptance that renewed and brought him the greatest sense of strength imaginable, each soothing breath of his harmonica being a warm hug to his former self. His wounded soul began to mend as he exorcised his demons, and feeling stronger than ever, he took a deep breath and looked outside for the very first time.

However, the conclusion of his ditch period did not mark the end of his depression. As songs like “Revolution Blues” or breakup albums like Homegrown showed, he still had periods where difficult times returned and had much to deal with. The difference is that he was strong enough to never compromise himself for others anymore and could bring everything back into the big picture. A year after the ditch period, he released Zuma, American Stars ‘N Bars, and Comes a Time, albums that showed further developments of his more soulful and countrysides even if those styles were outdated by the late 70s. He was able to still create artistic works of epic proportion on his confident final LPs of the decade Rust Never Sleeps and Live Rust, albums where he channeled the collective disillusionment of his time to bring classic rock to a cathartic finish while pioneering grunge at the same time. For the rest of his career, he felt, at last, he was free to do anything he wanted artistically, and even if times got tough once more, he would have his guitar standing by him the whole way through.It's through his period of despair and suffering that he realized that the chaos of life is not something to reject or fight but to embrace. No matter how much we might hate it, life is intrinsically chaotic, where times of great joy and pain will strike when least expected. It is easy to simply be reactionary and take everything based on face value alone. With the hardship Neil Young faced, he felt that being emotionally at the whim of chaos just isn’t a way to live life. For all the tragedies that he faced, his own music demonstrates that the world is so grand and magnificent, to the point where accepting defeat can only limit one’s ability to grow. Young tamed his own chaos and turned it into music that changed the lives of countless listeners in the process. It’s through unlocking the raw human spirit that we can find meaning in such a turbulent world, yet isn’t it this imperfect beauty that gives life meaning? All that’s clear is that as long as recording music is available, Neil Young’s classic period will serve as a testament to the sheer power of human strength to not only survive the toughest of circumstances but to turn pain into something tear-inducingly universalistic.

/https://www.therecord.com/content/dam/therecord/entertainment/2014/11/12/neil-young-s-overlooked-early-days-puts-canadian-author-in-spotlight/B821767820Z.1_20141112161430_000_GD31C4O90.2_Gallery.jpg)

Beautiful 👏

ReplyDeleteThank you so much! It means a lot!

Delete